Going on Tour with Absolute Genius CAITLYN PAXSON! Plus other stuff!

February is over, and with it all emergencies, surgeries, and recoveries. I am almost, in fact, full recovered. Which is good. Because a lot of stuff is coming up!

For FAWM—February Album Writing Month—I wrote lyrics to 9 songs (9 of the 14, so I didn’t “win” FAWM), and two of them garnered musical collaborations! But I’m into it! I want to do it again next year, possibly with my brothers, if they’ll agree!

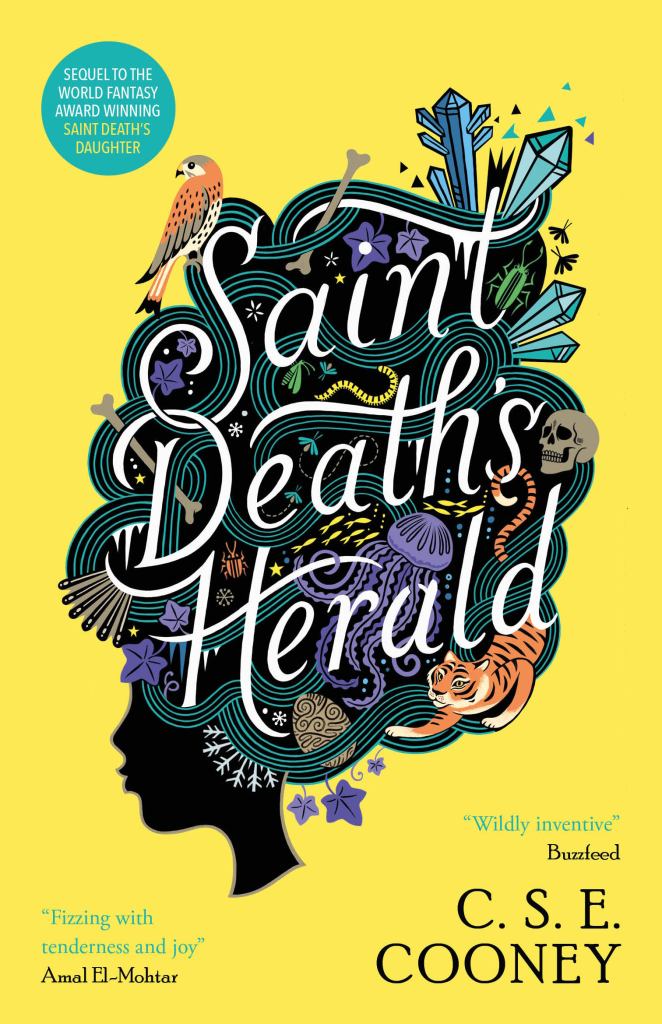

I also passed 50K on my novel wip, Saint Death’s Doorway. Trying to amp up the writing in March and get the greater part of the REST of it done.

Meanwhile, things are happening! This week, even. And beyond! BEHOLD!

Wednesday, March 11—Fantastic Fiction at KGB

A night of Fantastic Fiction with guest writers Kristina Ten and yours truly, C. S. E. Cooney

Saturday, March 21st—Negocios Infernales at Shore Gamers!

TTRPG game: 1-5 PM

Infernal Salon: 6-7:30 PM

Play the new TTRPG Negocios Infernales, run by game designers Carlos Hernandez and C. S. E. Cooney, at Shore Gamers in Red Bank, New Jersey! This will be followed by an Infernal Salon, open to all!

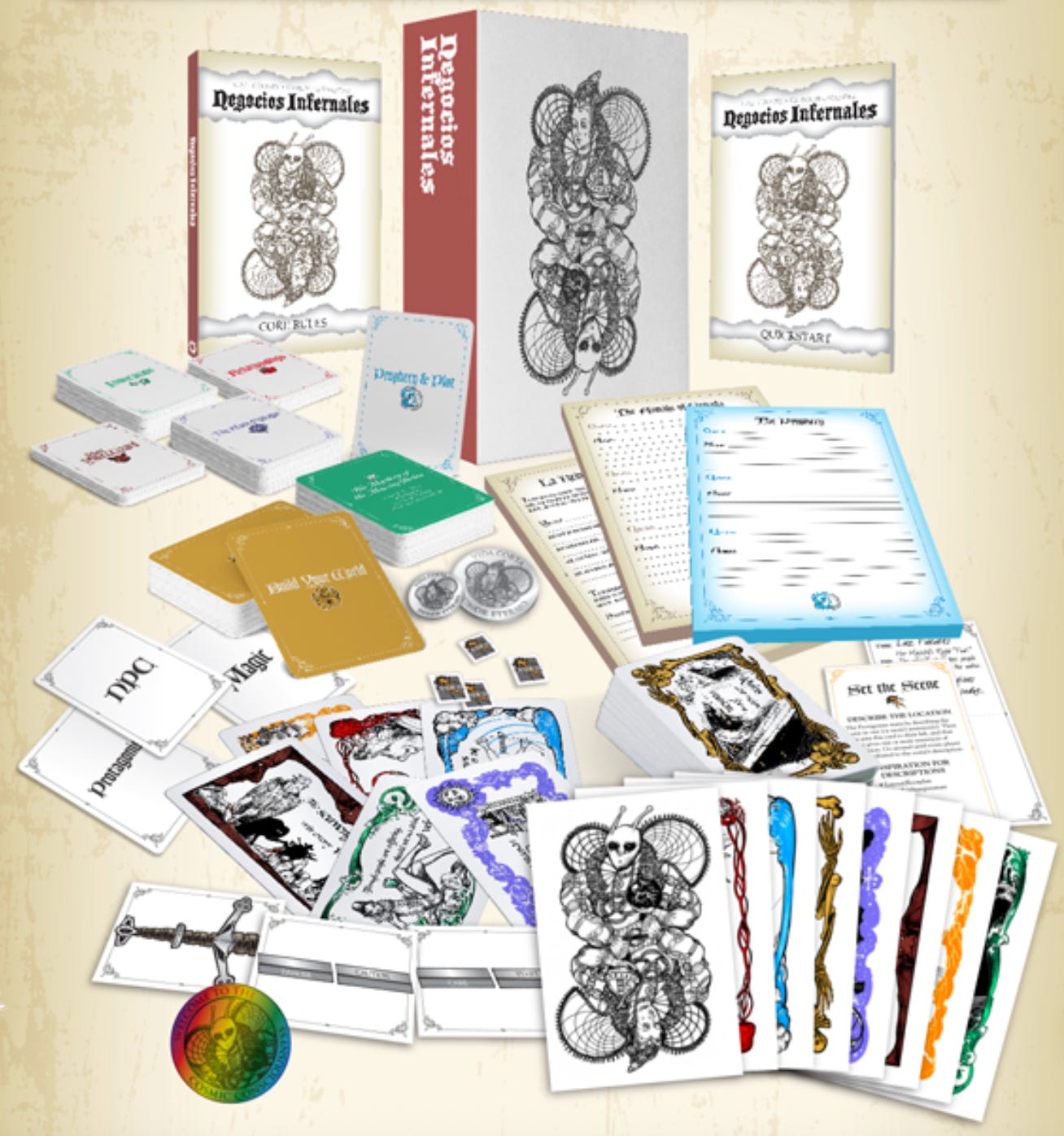

What is Negocios Infernales?

A DM-less, diceless, collaborative ROLEPLAYING GAME: “the Spanish Inquisition INTERRUPTED by aliens!” Play a desperate wizard who’s made a devil’s bargain: but the “devils” are ALIENS just trying to save humanity! Instead of dice, use weird, spooky cards to determine your fate!

What is an Infernal Salon?

A fun, low-stakes creativity workshop. You’ll draw one or more cards from the very spooky, PG-13 deck from the TTRPG Negocios Infernales. Then, we set a timer for 25 minutes, and everyone shares what they’ve made! Great for writers, DMs, musicians, and creatives of every stripe.

Monday, March 23—The Power of Poetic Imagination in Our Time

( RESCHEDULED from snowpacalypse)

A panel of poets at Saint John’s University: with Connecticut Poet Laureate Antoinette Brim-Bell, Rhysling Award-nominated poet Ali Trotta, and yours truly, C. S. E. Cooney.

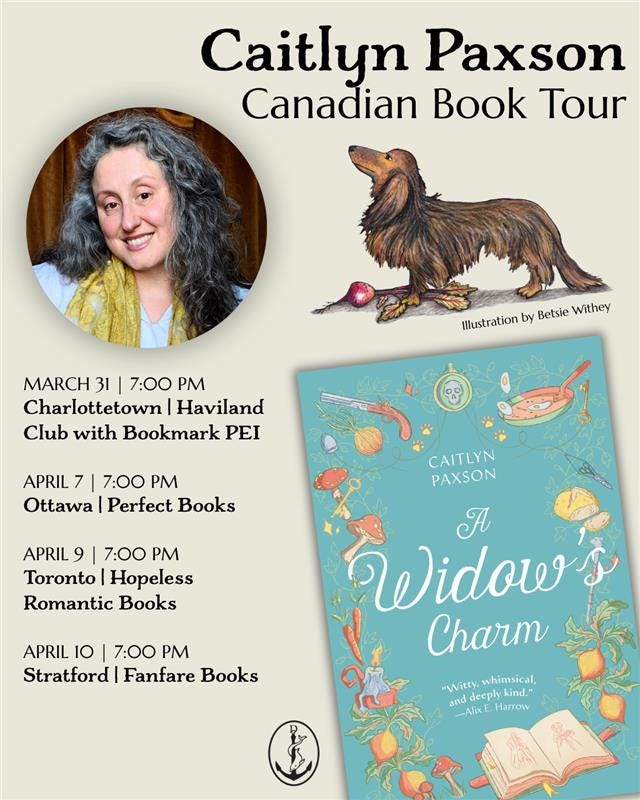

APRIL 7 – APRIL 20th

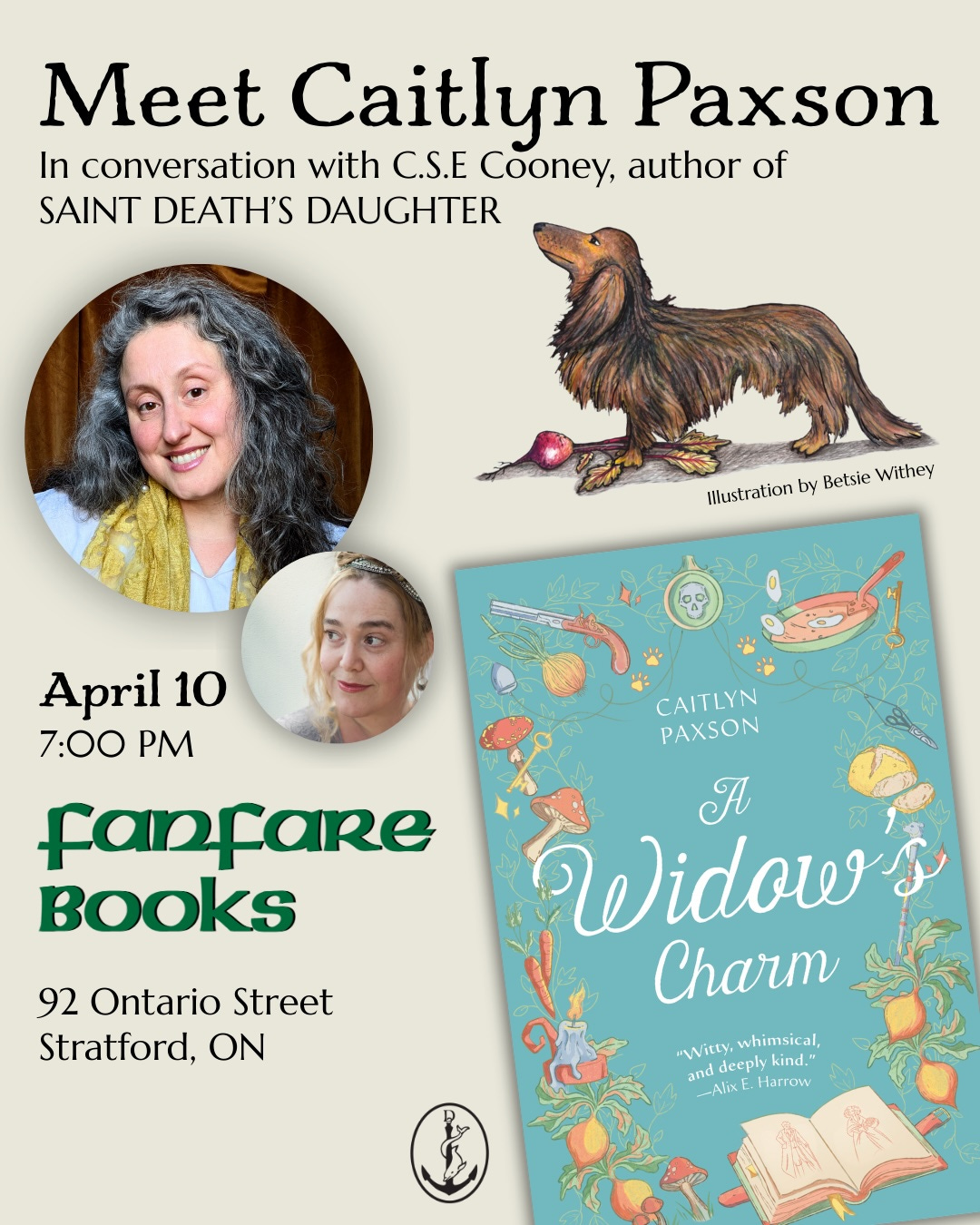

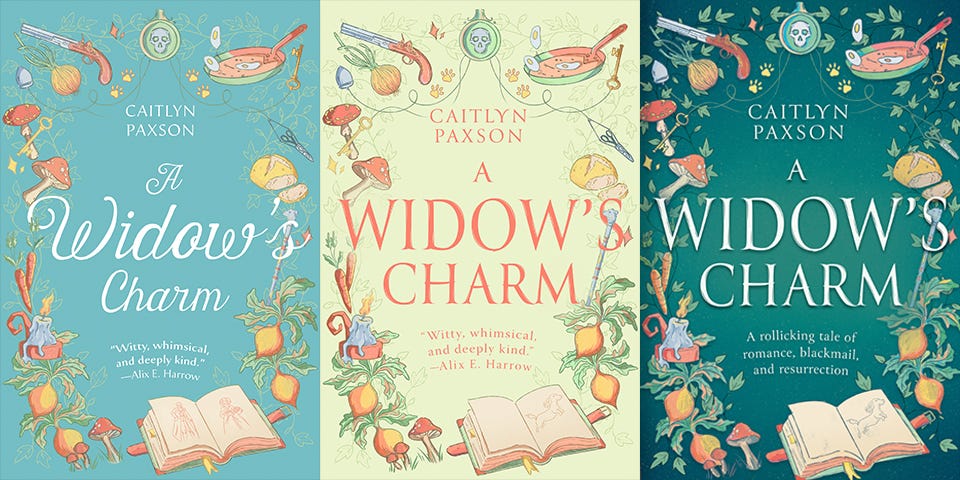

CAITLYN PAXSON’S BOOK LAUNCH TOUR FOR A WIDOW’S CHARM!

Caitlyn starts her tour in Charlottetown, P. E. I. on March 31st at 7 PM, with Haviland Book Club at Bookmark P. E. I. She writes:

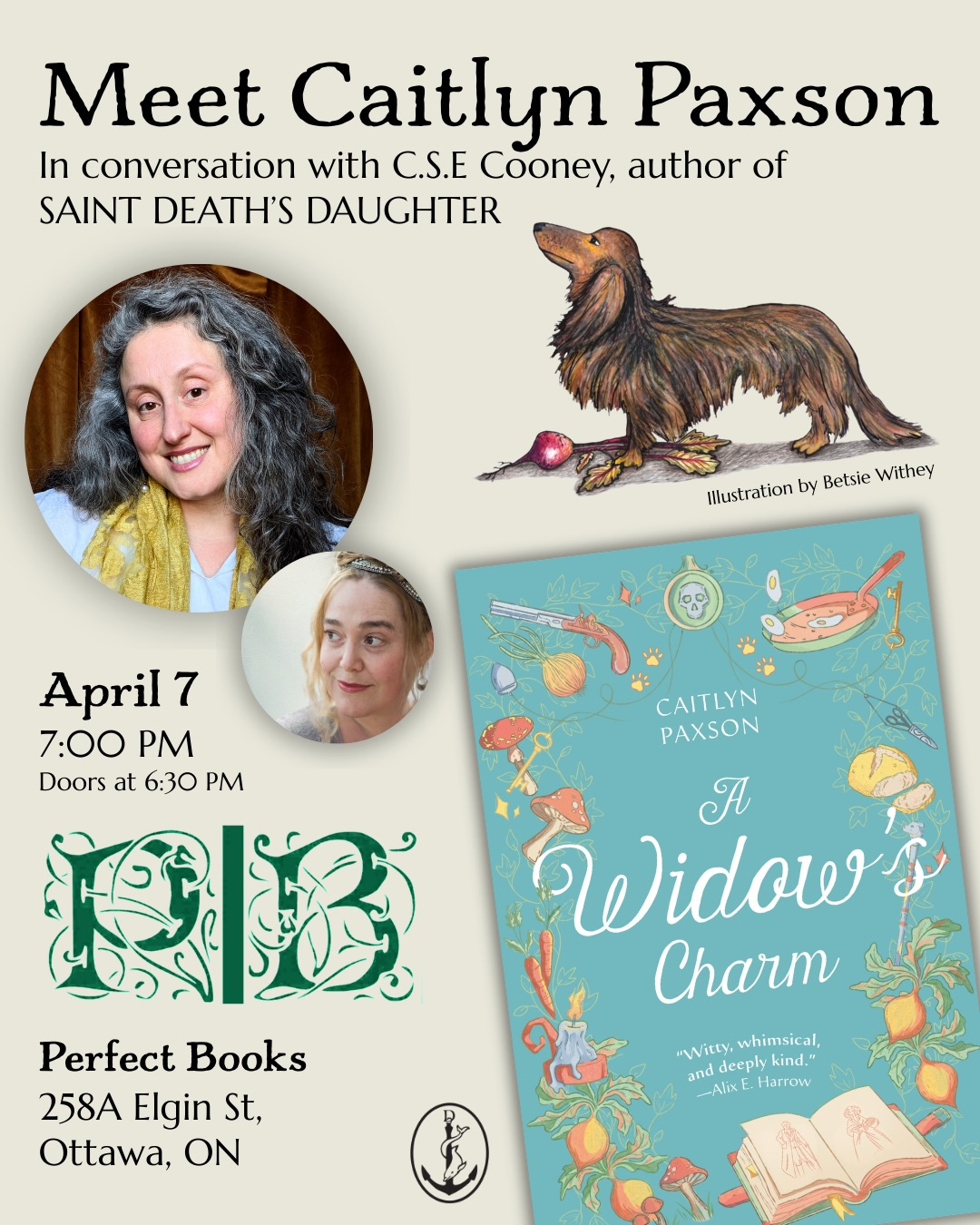

But then I have the UNUTTERABLE pleasure of joining her on the rest of her Canadian and U. S. book launch tour! I get to be her conversation partner and BASK IN HER GLORY!

Caitlyn writes:

I am so excited to chat with Claire at all the Ontario and US tour stops – besides talking about A Widow’s Charm, you can expect us to cover topics such as writer friendships and how they sustain us, creating loveable necromancers, and many other topics!

About A Widow’s Charm

In this witty fantasy romance, a widow attempts to resurrect her dead husband by blackmailing her rakish necromancer neighbor—only to find herself falling for him instead.

“Witty, whimsical, and deeply kind, A Widow’s Charm is beyond charming—it’s wholly enchanting.”

—Alix E. Harrow, New York Times bestselling author of The Everlasting

Lady Hildegarde Croft is accustomed to changes in position. After all, she rose from maidservant to lady of the manor when she married Lord Thorgoode Croft. But when he dies unexpectedly, the plans that would have protected her and the people of Croftholde die along with him. What’s a widow to do?

Potential salvation arrives in the form of Lord Elmwood, who is fleeing the consequences of using his forbidden Charm to raise the dead. Now he’s injured, destitute, and hiding out at the neighboring estate.

For Hilde, blackmailing Lord Elmwood to resurrect Thorgoode seems like the perfect solution. For Elmwood, beautiful Lady Croft seems like the ideal distraction from his troubles. The problem is, all she wants from him is the horrifying power he knows he can never use again.

My blurb for A Widow’s Charm?

“Caitlyn Paxson’s A Widow’s Charm is hair-raising, dead-raising, and utterly arousing. Sexy, absurd, cozy, lovable, hold-on-to-your-pants thrilling. The whole thing charmed the hell out of me. What even is this book? It’s everything I want to read!”

—C. S. E. Cooney, author of World Fantasy Award-winning Saint Death’s Daughter

About Caitlyn Paxson

Caitlyn Paxson has a degree in writing and cultural history and has worked as the artistic director of storytelling performances, a harpist, a book reviewer, a nineteenth century jack-of-all-trades, a shepherdess, and a fake Victorian spirit medium. She lives on Prince Edward Island with her husband and three orange cats. A Widow’s Charm is her first book.

CANADA TOUR

Ottawa, April 7th, 7 PM—Perfect Books

Toronto, April 9th, 7 PM—Hopeless Romantic Books—ticketed event link here

Stratford, April 10th, 7 PM—Fanfare Books

U. S. A. TOUR

Traverse City, April 12th, 2-4 PM—Artemis Books and Goods

Chicago, April 17th, 6:30-7:30 PM—CityLit Books (ticketed event link here, book included!)